Long-Term Expected Return of Collectibles

Executive Summary

- Stores of value represent an alternative asset class compared to stocks, bonds, and real estate. Examples include gold and silver bullion, many cryptocurrencies and NFTs, collectibles, and art. Stores of value do not generate income, and while most have some utility, their primary financial use is to hold value over the long-term in line with inflation and global wealth.

- Gold bullion and gold jewelry make up most the store of value market cap at $12 trillion. The global art market is valued at over $1 trillion. The crypto market recently peaked at $2.9 trillion. The global collectibles market is much smaller, in the $500 billion range. By comparison, the global market cap of bonds, stocks and real estate are many multiples of world GDP, on the order of $500 trillion.

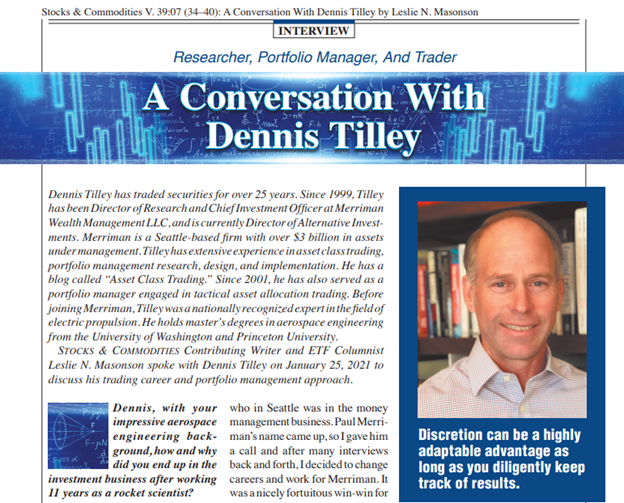

- The current investment environment is favorable to stores of value as a partial replacement for bonds as part of a diversified portfolio. Store of value assets provide inflation protection, portfolio volatility moderation, and should outperform treasury bonds over the next decade as the Fed holds rates below inflation. Store of value assets are also underowned among U.S. investors, compared to the massive wealth invested in financial assets.

- Collectibles and art have historically produced real returns of 2-3% before transaction costs, which is much better than prospective government bond returns. Collectibles and art are also unquestionably a climate-friendly asset, which can’t be said for crypto or the gold mining complex.

- Collectibles and art are not suited for a managed fund format or as part of a professionally managed portfolio. Low liquidity and high transaction costs force hold periods to be a decade or longer. Patient buying and selling is a must, which is generally not allowed with funds owned by pools of investors. Fund management fees would likely be high and seriously dent the benefits.

- Collectible investments must be personally held, which has many pitfalls. An investor must dedicate a lot of time to understand the field, the pitfalls and how pricing and grading works. For most investors, this is not worth the effort. For a passionate collector, or sophisticated asset class trader, investing in this space could be nicely profitable over the next decade.

Introduction

Introduction

Each store of value has its pros and cons compared to others. All require a fundamental belief or leap of faith that future buyers will pay ever rising prices. Gold has served as an excellent store of value for many millennia, yet most investment advisors and institutional investors shy away from a gold allocation. There’s no income, and it seems so backward to value a shiny yellow metal so highly. Yet gold is highly liquid and has returns that are uncorrelated with stocks and bonds.

Professional investors are inching their way into cryptocurrencies, pushed by their clients and FOMO, even though crypto is so new and excessively volatile. Bitcoin, the largest of them, is viewed as an improved digital gold because supply is capped at 21 million bitcoins. Digital gold also comes in the form of a low-expense ETF holding gold bullion in a bank vault. Yet, gold supply is expected to grow forever, which caps long-term expected returns.

A third class are collectibles and art. Collectibles, art, and various rarities have a long history of holding value. U.K. auction houses Sotheby’s and Christie’s were established centuries ago, in 1744 and 1766 respectively, to serve collectors and investors in this space.

The adage among financial advisors is that collectibles are not an investment. This is generally good advice. Yet, the collectibles asset class has attracted a resurgence of investor interest since the global pandemic emerged two years ago. There are many reasons for the renewed interest and rising prices.

First, new innovative technologies and platforms have greatly increased access and attracted attention. Collectible fractional ownership platforms such as Collectable, Dibbs and Rally are growing rapidly. A new art form and collectible technology, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and platforms to purchase and hold NFTs such as OpenSea, have exploded in popularity with over $40 billion in sales in 2021.1 These platforms allow a user to own a portion of a rarity and conveniently monitor holdings on their phones.

Another reason to pay attention to this asset class has been the massive increase in crypto, real estate and stock market wealth, which is feeding into the demand for digital art, collectibles, and all sorts of rarities. Wealth growth drives the demand for rarities. In a sense, investing in collectibles is a bet on the continued growth of private wealth in America, a bet that may zig and zag differently than stocks and real estate.

The uber-rich have more than enough resources to support their lifestyle, and thus we expect some of their wealth to ultimately find its way into various rarities and stores of value. With respect to storage and hassles, it’s much easier to diversify away from paper wealth with gold, compared to buying ten homes, 50 cars, a private island or a few yachts. You can’t take that wealth with you in a hurry. Art was the primary collecting interest of American tycoons in the 1800s. Since the mid-1950s, collectibles have emerged as a competing asset class.

Conventional investment management thinking also has more investors seeking inflation protection as government debt-to-GDP ratios and deficit spending are at all-time highs throughout the developed world. Inflation may be the only palatable “tax increase” governments can use to reduce debt-levels over time. Collectibles and all stores of value have a history of being good inflation hedges.

Another means to slowly lower debt-to-GDP levels is to hold government bond yields below inflation. This central bank action is often called financial repression. I fully expect government interest rates at all but the longest maturities to stay below inflation over the next decade or longer. The U.S. is not alone in being stuck with ultralow interest rates. Japanese yields have been near zero for two decades and the Eurozone has experimented with negative interest rates for ten years. Figure 1 shows a chart of the real U.S. Fed funds rate over time.

Figure 1. Real Fed Funds Rate in the Post-War Period.

The Fed is stuck in a box. I’m sure they’d like to increase interest rates to a level where conventional monetary policy can once again be used to manage the economy and inflation. I’m sure they’d like to unwind their balance sheet significantly. Unfortunately, significant interest rate hikes and/or quickly unwinding the balance sheet will likely be met with equity bear markets, falling real estate prices, recessions, spiking unemployment, and much more of the U.S. federal budget shifted to paying interest. No one wants any of that, so I don’t expect the Fed chair to jeopardize their job by raising rates too high or too quickly. Also, when the inevitable recession does occur, expect short-term rates to quickly fall to zero once again.

With such a backdrop, government bonds look extremely unattractive. Total returns net of inflation will be negative even if rates remain range bound over the next decade. Investors at all levels are searching for an alternative to bonds; in particular, an asset that can deliver small but positive real returns while also serving as a portfolio ballast during equity bear markets. Gold was discussed in a previous blog post.2 For this article, I’ll assess that long-term expected return for collectibles and rarities such as art, sports memorabilia, rare stamps, and rare coins.

Proponents of collectible investing suggest equity-like returns uncorrelated with stocks and bonds. Such claims are often misleading based on short periods of historical returns while ignoring numerous costs and fees. More care is required to assess long-term expected returns using many decades of data.

Fortunately, there are a few good academic studies addressing this question. Long-term expected real returns of art and collectibles are in the 2-3% range. That’s better than gold at 0-1% net of inflation, better than bonds (in normal times) at 0.5-1% net of inflation, but lower than stocks at 5-6% net of inflation. Later in this article, I’ll review the historical evidence and the simple reasoning for collectible expected returns.

Looking forward, stocks (especially U.S. stocks), bonds, and real estate all look expensive and overowned.2 Indeed, compared with GDP, market caps of all three major asset classes are at levels never seen in history. Store of value assets are underowned on a secular timescale just as inflation is reemerging and real interest rates are expected to be significantly negative for many years to come. A real return of 2-3% is very attractive as long as the correlation with equities remains low. The process of investors diversifying away from financial assets, and adding to the store of value asset class, should push collectible pricing higher and produce attractive returns over the next decade.

Non-Financial Social Returns

Unlike buying bitcoin or gold, the world of collectible and art investing offers more than financial returns. For passionate collectors, there is fun and satisfaction in slowly building a collection, learning about the history, and being part of the hobby’s social sphere. National conventions can bring the like-minded together, and bidding in auctions can be exhilarating.

There are no ETFs for this asset class, so allocating capital takes time. Each purchase is like a mini long-term investment. Learning about the ins and outs of the hobby can also take considerable time. Understanding the grading process as well as pricing nuances is essential. Effort must also be made to minimize the potential for “black swan” losses due to fraud, theft, and disaster.

Ownership of collectibles can also serve to signal wealth and status, which most humans seem to like. Everyone loves bragging rights. A previously unknown rich person can become instantly famous and enter their name in the history of the field simply by being the highest bidder or amassing the biggest collection. Proceeds associated with an eventual sale can go to charity, thus gaining karma points and social praise.

Finally, collectibles and art are the green investments in the store of value space. Cryptocurrencies use excessive amounts of electricity. Gold mining also generates greenhouse gases, at least for the new supply. Much like existing gold stock, collectibles do not contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Long-Term Returns of Gold

To determine how collectible prices grow over time, lets first start with gold – the safest store of value with the longest history of inflation protection. As of 12/31/2021, the world’s supply of gold is worth about $12 trillion, which is an order of magnitude greater than the bitcoin market cap at about $0.9 trillion. The world art market is estimated to be about $1 trillion and the world’s collectibles market is estimated to be worth $300-$500 million.3,4

Over the past 500 years, gold has delivered a historical return that roughly matches inflation.2 Thus, a real return of 0%/year or CPI + 0% as I sometimes say. This makes sense, as with all commodities, that price trades near the marginal cost of production, which increases with inflation over time. New gold supply, produced by the world’s gold miners, has grown at a rate of 1.6% a year over the last 100 years. At times new supply has been a low as 1.2% and as high as 1.9%. New gold supply is not responsive to demand shifts due to the long-term nature of developing gold mines.

Interestingly, the U.S. dollar gold price has gained 1%/year in real terms since 1900. Most of that growth occurred when the world shifted to a fiat currency system in the early 1970s. Real GDP growth has been about 3% per year, thus the difference is about what annual production has been since 1900 (about 1.6%/year). Since 1970, residential home and land prices have also grown at rates above inflation, which may reflect the immense growth of financial wealth associated with stocks and bonds pulling the value of gold, collectibles, cryptocurrencies, homes, and land up at rates higher than inflation.2

The idea that aggregate wealth growth drives demand for stores of value is fundamental to expected returns. Investors are expected to diversify a small portion of their assets into stores of value. How investors parcel assets among the stores of value will vary over time. So far, in the history of finance, gold has not become obsolete as a financial asset, even though it’s been known as the “barbarous relic” among many famous economists for almost 100 years. The entrance of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to the scene is another potential threat to gold being the premier store of value.

Model of Expected Financial Returns of Collectibles

Collectibles and art hold a nebulous rarity premium above and beyond the materials cost associated with the item. Expecting a collectible to hold value over time does involve a leap of faith, but most investing does. Attempting to understand and apply logic to relative pricing can be very frustrating. For example, a banana duct taped to a wall sold for $120,000 at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019.5 A good story can increase value, including a story of something selling at an absurd price.

In the collectibles space, rarity most often trumps beauty and popularity, but for many items popularity or an “IT factor” is more important than beauty, historical significance, and rarity. Prices can be anchored at high levels for decades. Ultimately, collectors want confidence that an item can be sold at a higher inflation-adjusted price in the future, and thus seek items with a combination of rarity, consistent and high demand from collectors, historical significance, and a history of high prices.

While relative pricing can be confusing, price increases over time do seem to follow a general rule over the long run. Compare the gold supply dynamics with the premier rarity in each collectible universe – the one-cent magenta postage stamp, the best-conditioned Honus Wagner T-206 baseball card, the rarest and most sought-after rare coins, and masterpiece paintings. These are one-of-a-kind highly desirable rarities. As global wealth grows over the decades, there is no additional production of such an asset.

Thus, we expect prices of such rarities to grow over the decades with national and/or global wealth growth rates. Since wealth generally grows with gross domestic product (GDP), we expect:

Annualized Return of High-End Collectibles ~ Annualized Return of GDP

Historically, GDP has grown 5-6% in most developed countries, or 2-3% after inflation. The equation above definitely shows the direct inflation protection provided by collectibles. The run-up in collectible prices as inflation peaked in 1980 is one example of this relationship.

The equation also shows how the growth in wealth has a gravitational pull on the store of value market cap. As the market cap for stocks, bonds, and real estate grows over time, the need for stores of value also grows. With gold, price increases are moderated with new supply. With top-shelf collectibles, only price can grow to keep up with global wealth.

Of course, there are many factors that strongly affect realized returns over a long hold period, including:

- Relative attractiveness of collectibles compared to other asset classes such as stocks, bonds, gold, and real estate.

- Trends in wealth inequality, the geographic distribution of wealth, and wealth/GDP.

- Changes in preferences and popularity of a collectible compared to other and newly emerging collectibles and stores of value.

- Novelty/adoption premium associated with a new collectible.

With respect to buy and sell execution:

- Purchase and sales fees, such as buyer’s/seller’s premiums charged by auction houses.

- Carry costs such as storage, insurance, time, maintenance costs and investment fund fees.

- Buy price compared to a long-term intrinsic value.

- Sales price compared to a long-term intrinsic value.

Factor 1 suggests that the store of value asset class must be compared with the attractiveness of other asset classes.2 In 1980, many collectibles and gold were trading at extreme valuations as investors chased returns and worried about runaway inflation. Yet at that time, stocks and bonds were incredibly cheap. In 2000, gold was cheap, and stocks were expensive. Currently, it appears that stocks, bonds, and real estate are all very richly priced compared to store of value assets.2

Factor 2 suggests a positive correlation of high-end collectibles with equity markets, and that is indeed seen in historical data. Many collectibles and art markets peaked in 1990 (Japanese Bubble) and in 2008 (the Great Financial Crisis). Dimson and Spaenjers suggest that all collectible price indices greatly understate true price volatility due to infrequent trading and appraisal-based pricing. This is identical to comparing the volatility of privately held real estate with REITs and comparing private equity with publicly traded equity indexes. Unsmoothing returns suggest that collectibles have equity-like volatilities and a higher correlation with stocks.6

Essentially all investors like the idea of adding privately-held equity assets to smooth portfolio returns. This diversification benefit is not illusionary. There are many equity bear markets that don’t affect private valuations. During the 2000-2002 bear market, private real estate values and most collectibles were unaffected, while the stock market lost over 50%. In these cases, the diversification benefit is real. Another advantage of private assets is they can’t be sold easily, which can keep investors in the game during periods of stress. Equities can be easily sold by a scared investor in a panic, which usually leads to later regrets.

Factor 3 suggests that buying and holding a collectible that ultimately goes out of style can be costly. Wealth demographics change, and new tastes can affect returns. Dimson mentions seashells as a previously highly valued collectible in the late 1700s.7 Many collectibles fail to establish themselves among rich collectors. Beanie babies is one example. Even ancient coins and art, which have been valuable for centuries, can go out of favor during a lifetime.

Factor 4 indicates that finding an emerging collectible, just like finding an emerging start-up or artist, can produce immense returns. Lately, many new stores of value have entered the space, including cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and video game cartridges.

Factors 5 and 6 represent the significant costs of buying, selling, and holding collectibles. Most collectibles are illiquid. Prices can move considerably when only a few buyers are interested. Collectibles also take considerable mental time to research, buy and sell through either a dealer or auction. Some purchases have sales taxes.

Transaction fees in the collectible space are very high, which effectively pushes hold times to a decade or longer. U.S. rare coins, with a huge dealer network, typically have a bid/ask spread of 20-25% around the mid-price. Auction houses charge buyer’s premiums of 15-20%, which essentially reduces the sales price compared to the mid-point fair value price. Acting like a dealer or market maker in this space can help minimize these costs.

Some collectibles have significant carry costs. A collectible automobile must be serviced and maintained. All must be safely stored and insured. For art and wine, storage and insurance costs are estimated to be 0.5%/year.8 For storable rarities such as rare coins, stamps, and trading cards, storage and insurance costs should be very low (~0.1%/year).

Finally, Factors 7 and 8 account for opportunistic and/or unwise purchase and sales at prices below or above a theoretical and unknown long-term intrinsic value of the asset. Buying into a rush of rising prices, or near a bubble peak will dramatically reduce long-term returns. Buying at highly depressed prices and selling into a bubble ten years later can offer superior returns.

Shown in Figure 2 is the growth of a U.K. Stamp Index (in orange) net of inflation versus real U.K. GDP growth (in blue) both indexed at 100 in 1899.6 It’s impossible to know the true long-term intrinsic value of a collectible at a given time, and it depends on more than just GDP level. Yet, common sense suggests that when the U.K. Stamp price index diverged far from the GDP line, that perhaps prices were due to mean revert. Certainly, in 1980 U.K. stamps appeared to make a bubble top, much like many inflation hedging assets. Any parabolic blow-off top is likely far above intrinsic value. Alternatively, after stagnant prices for a decade or longer, we could guess that prices may be at or below intrinsic value.

Figure 2: U.K. Stamp Price Index from Reference 6. Pointwise estimates made after 2007.

To summarize, the following formula can be used to estimate future annualized returns (R):

where n is the hold time in years, D% is the bid/ask spread as a percentage of the mid-point price, Rnom GDP is the nominal GDP growth rate which can be very high during periods of high inflation. CC% represents the carry costs as a percentage of value over time. The ratio of P/IV is the purchase or sales price compared to long-term intrinsic value at the time. While IV is unknowable, we can make an educated guess that it rises smoothly over the long-term with nominal GDP.

Selling rarities into a blow-off top may also allow a collector to sell near an ask price, rather than hitting a bid. Buying when everyone is selling may allow a collector to buy near a bid price, rather than at the ask. Patience and “buying right” are critical for achieving decent returns in this asset class. And as an asset class trader, we can always look to other asset classes when capital can’t be deployed efficiently in the collectibles space.

The above equation also suggests why a pooled fund structure holding collectibles will likely underperform. A long hold time, n, is required to minimize the impact of transaction costs. Most private fund structures avoid hold periods greater than 10 years. Funds holding pooled assets will generally be forced to buy and sell with investor flows or due to an arbitrary liquidation date, which is the opposite of being a patient trader. Plus, fund providers will want to charge a management fee of 1-2% per year and likely a cut of the profits, which seriously eats into long-term expected returns. Fractional ownership platforms, such as Collectable, can potentially sidestep many of these issues.

Historical Evidence

We need to examine the returns of collectibles with a long history of prices. Comic books, sports memorabilia and trading cards do not have a long history and shorter return periods benefit from the novelty premium. Even with considerable pricing data, such as with U.S. rare coins going back to the 1950s, the effect of improved standardized grading can dramatically enhance returns of the highest graded items, and depress returns associated with lessor samples. These are one-time return effects.

We must also acknowledge that survivorship bias may creep into results. Many original works of art are purchased, yet resale value falls over time when the artist never becomes adopted by collectors. There may be 100% loss on such investments. Other collectibles are hot for a while, yet don’t have the staying power to generate lots of auction activity and sustain the interest of collectors over decades and centuries. Examples from a century ago or longer include tulips, seashells, and souvenir silver spoons. Since the 1950s, Hummel figurines, vinyl records, Thomas Kincaid paintings, and beanie babies have all lost their luster among high-end collectors.

Figure 2 shows the real price of U.K. stamps since 1900 compared to real GDP. This index is constructed using the most expensive U.K. stamps, and thus the premier rarities in the philately field. From 1900 to 2021, the real U.K. Stamp Index grew at 2.9% per year compared to 2.1% real U.K. GDP growth.

Figure 3 shows the real growth of an Art index constructed with repeat auction sales of top tier art works over the last three centuries.9 Since 1765, the Art index has grown at a rate of CPI + 3% in British pounds. Notice how prices peaked at various stock market peaks in financial history. Indeed, since this study, art also peaked in 2008, and has fallen about 50% net of inflation since.10

Art was the name of the game among the ultrarich in the 1800s, and it appears the growth rate outpaced the long-term average up to the 1873 financial panic. John Pierpont Morgan held a considerable fraction of his wealth in art when he died in 1913.11 Perhaps there was a bit of novelty premium in that growth. From 1873 to 2007, the art index is up about 2% real, which is identical to the U.K. GDP growth rate during that time frame.

Figure 3: Yearly Real Art Price Index in GBP from Reference 9. Index value in 1765 is set to 1. This chart shows the growth in art values net of inflation.

The next chart, Figure 4, comes from the 2018 Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook.8 The chart shows the real returns of various rarities from 1900-2017 in US dollars (USD). Over that time U.S. GDP grew at 6%/year while inflation was 3%/year. The average of all the collectibles was CPI + 2.9%, while stocks delivered CPI + 5.2%. Art grew at 1.9% real, stamps at 2.6% real, violins at 2.4% real, and fine wine at 3.6% real. Note that indices for jewelry, autos, and books do not go all the way back to 1900.

As seen in both Figures 3 and 4, there was a Great Leveling12 in wealth that occurred during the two world wars and the Great Depression. Global wealth as a percentage of GDP fell, along with a dramatic reduction of wealth inequality. Figure 4 also shows that while collectibles and art held their value versus inflation, they were cheap by the 1950s, along with equities. We can assume that all collectible prices in the 1950s were priced below long-term intrinsic value.

Figure 4. Real returns of various rarities in USD. From Reference 8.

Figure 4. Real returns of various rarities in USD. From Reference 8.

Recent stamp auctions show similar results. The most expensive stamp in the world, the British Guiana 1-cent magenta was auctioned on June 8, 2021 at a price of $8,307,000 at Sotheby’s. Almost 100 years ago (in 1922) it sold for an astronomical $32,000. That’s an annualized return is 5.8% per year matching U.S. GDP growth.

In the U.S., famed PIMCO bond king Bill Gross sold a significant portion of his stamp collection in multiple auctions between 2018 and 2020.13 Like-item sale prices going back to the 1880s are shown in Figure 5. To produce this chart, I selected eight historical items with extensive provenance and indexed recent sales to 100,000. An exponential line fit shows price growth at 6.2%/year while U.S. GDP grew at 5.7%/year during that 133-year period.

As a final example, Figure 6 shows a price performance table for a representative sample of U.S. proof silver coins with moderately low mintages (~1000). Data is obtained from PCGS, which has extensive price information for rare coins of many grades and price levels going back to 1970. The grade for each coin was chosen to represent a quality rank of about 20-80. Since 1970, returns for these moderately priced coins have grown on average 6.9% per year which is well aligned with 6.3% U.S. GDP growth and the 7.5% growth in U.S. household wealth. Moderately priced rare coins suffered a 30-year bear market since the slabbed-coin bubble of 1989. Now prices are perking up after a long slumber, and perhaps they trade below intrinsic value.

Figure 5: Historical sale prices of select U.S. stamps and covers indexed to 100,000 in 2018 and 2020. Data in reference 13.

Figure 6: Price performance of U.S. Silver Proof Coins with estimated quality rank between 20 and 80. Data from PCGS and links supplied in chart.

What about sub-tier collectibles?

So far, we have shown historical returns of premier collectibles, often one-of-a-kind and highly desired, which currently trade at prices greater than $100,000 and often in the millions. But what about collectible pricing when there are thousands or even millions of specimens? There is a saying in the industry that the keys to buying collectibles is “condition, condition, and condition”, much like “location, location, location” in real estate. Such an axiom is especially the case when professional grading is used to create conditional rarity among collectibles that have tens of thousands of samples.

Systematic professional grading got started with rare coins in the mid-1980s. This new technology allowed investors and collectors to buy standardized graded coins sight-unseen. There were many pitfalls with this approach, but enthusiasm around slabbed coins created a massive bubble peak in May 1989, which most rare coins have yet to surpass. Nowadays, many collectibles such as baseball cards, comic books, and video games are graded for pristineness which allows collectors to rank the best samples and use population reports to assess rarity.

Graded collectibles have a pricing structure that varies exponentially with grade quality. This was not the case before professional grading. Now the very best grades trade at an enormous premium, as wealthy collectors pay up for the very best and highest quality specimen. At the other end of the spectrum, there are many casual collectors holding average-quality collectibles such as baseball cards and comics with huge population counts. Such a collection holds very little rarity value and is unlikely to interest a professional dealer.

There is a middle ground, for collectibles trading in the $500-$10,000 range, that can certainly be used for investment purposes. Logic and carefully analyzed historical data suggest that similar long-term returns can be realized from these mid-tier collectibles. The table of proof silver coin returns in Figure 6 is one example.

What are the mechanisms to ensure similar long-term returns? First, collectors and professional dealers are keen assessors of relative value. Often samples that are graded one level below the top grade are still of excellent quality, and thus their prices tend to move in line with top-tier prices. Just as with real estate, pricing and appraisals of value are greatly influenced by recent sales of similar graded samples.

Collectors, investors, and dealers also perform relative assessments among the many different collectible types, thus ensuring this arbitrage mechanism can equalize long-term returns among many different types of rarities. At least in theory this should be the case, but in practice, the arbitrage process can be very slow.

Second, if top-tier pricing was truly expected to outperform over decades, the price gap between grades would become absurdly unstable. Collectors would be ever tempted to sell the highest graded sample and buy the next lower graded sample at a tiny fraction of the price. Perhaps, some sort of destruction arbitrage could become profitable to arbitrage steep relative pricing based on rarity.

Third, the mid-tier space makes up the bulk of the collectibles market cap and annual sales. While the highest-priced million-dollar items capture the headlines, their natural rarity means unit sales and quantity are quite low. Alternatively, expensive “investment quality” second and third tier items account for most of the market cap and sales. For example, see Figure 2.6 in reference 3 for the global art market. The lower the price point, the higher the total annual sales.

Finally, lower-priced collectables are more affordable for a larger number of collectors. There should be more demand for the mid-tier collectibles. Again, to emphasize, I’m talking about collectibles priced in the $1000 to $10,000 range. The box of 1980s heavily handled baseball cards in the attic are not worth much.

The bottom line is that we expect mid-tier collectibles to have similar long-term expected returns as the rarest high-end collectibles. We also expect prices of mid-tier collectibles to zig and zag differently than the million-dollar rarities. Often during price bubbles, when retail interest is immense, the low-priced product has the best percentage returns, although starting at very low base prices. We also expect secular trends to emerge from time to time that favor mid-tier collectibles, much like periods when starter homes outperform mansions, or when small cap stocks outperform blue chip large cap equities.

What about new supply?

Another issue we haven’t discussed is new supply. Every year, the supply of collectibles and art increases as artists create more content, governments mint more coins and stamps, and another year of sports memories are created. Most of this product has little rarity value, since all samples are of high quality, and many pristine samples are snapped up by collectors. New product providers often attempt to manufacture rarity with small limited-edition versions.

Another potential supply source is the repricing of collectibles produced a generation ago, as investors with money bid up childhood memorabilia. This is happening now with video game cartridges.

I suspect, but I’m not sure, that the annual new supply of rarity value is small (much less than 1%) compared to the size of the global art and collectibles markets. Historical returns, over decades and centuries of new supply, show that top-tier rarities are unaffected by new supply.

Of course, this doesn’t rule out the emergence of a new collectible form (such as NFTs) that may stunt future price growth of existing collectibles. There’s no doubt the emergence of cryptocurrencies over the past decade has stunted gold prices. This is just one of the risks of investing in stores of value.

Final Thoughts

In context of being an asset class trader, we must be open to possibilities in all asset classes. All stores of value look attractive at this time as inflation is reemerging, financial assets are heavily overowned and expensive, and real treasury yields are expected to be negative for the next decade. It’s hard to predict which store of value will do best in the future, so diversification is prudent.

Collectibles may be a good financial combo with gold and crypto assets. Gold is the ultimate safety asset in the store of value space with the lowest expected returns, but with returns that continue to be uncorrelated with stocks and bonds. Crypto assets are high reward/high risk stores of value, with equity correlations that continue to grow. I have no idea how much more adoption premium is harvestable in this space. Collectibles offer good long-term returns with additional social benefits such as being the only truly green investment in the store of value asset class. Any combination of the above may be of interest to investors.

Collectibles and art have historically returned 2-3% after inflation with little correlation with stocks and bonds. That’s very attractive in the current environment. Investing in collectibles is not for everyone. The process takes a lot of time and hold times must be a decade or longer. You’ll likely need to become a quasi-expert in the field and building the collectible portfolio can take years of patient buying. While most investors should avoid the asset class, there are multiple valid approaches to investing in collectibles, art, and other rarities.

- If you’re super passionate about a particular collectible, or you’re already a savvy collector, then I believe now is the right time to splurge on some of those high-end items you’ve always coveted. Another thought is to enter the field as a new career or entrepreneur.

- If you’re seeking to make a name in a particular field and you have the financial resources to bid on the very best rarities, then now may be the time to jump into the arena.

- If you’re a high-net-worth investor seeking to diversify out of bonds into more productive assets, then collectibles might be worth a small portion of a very diversified portfolio with the intention to hold for at least a decade or longer. Minimizing implementation costs will be key.

- If you’re a go anywhere asset class trader, then collectibles may be an interesting long-term investment to be held in the store-of-value bucket. Again, implementation is key, and the expectation is to hold for at least a decade. In addition, many asset class trading edges can be utilized to further enhance returns. One trading edge is to act like a dealer or market maker to provide liquidity and take advantage of the large spreads. Being ready to sell into parabolic price increases, and buy into panic selloffs, is another edge. Asset class traders can also exploit stale pricing to enter or exit the collectibles space during or after a major equity bear market. Finding undervalued collectibles may enhance returns. And of course, allocating capital to more conventional asset classes when there are few opportunities in the collectible space makes sense.

Transaction costs can be minimized by being agnostic about what collectible is purchased. Submit limit orders for many potential buys. Try to bid at a price below the mid-point of the current spread with auctions. Negotiate better prices with dealers. Buy when prices are sinking, and other collectors want out. Buy when no one is interested. Avoid chasing prices higher except in rare cases. Have the conviction to buy when prices are falling. Keep the allocation to collectibles small enough so you never have to sell.

Seek collectibles that appear to be trading below intrinsic value. Crypto prices have grown exponentially over the past ten years. NFTs have spiked by multiples over the past year.1 Trading card prices have spiked during the pandemic as indicated by the various indexes published by Card Ladder. Waiting for a good correction in the above markets may be warranted before investing. Perhaps hold gold while you wait, since gold prices have languished since peaking in August of 2020.

Older and more established collectibles are just starting to increase in value. Stamps and art peaked in 2008 and may be worth a look now. U.S. rare coins look particularly interesting and a good value. Prices of mid-tier rare coins peaked in 1989 at extreme valuations during the slabbed-coin bubble. Now, after falling versus inflation for the past 30 years, prices are starting to perk up. U.S. rare coins have many advantages over other collectibles. The dealer and auction market are the most active among all collectibles. Rare coins can be readily sold at any time. Pricing data for all coins go back to the 1950s, with extensive data going back to 1970. All investable coins have already been slabbed, so population counts are comprehensive. Coins are very storable, with minimal carry costs. Of course, a detailed understanding of the history of pricing and grading is essential for doing well in this asset class.

References

- Murphy, H. and Oliver, J., “How NFTs became a $40bn market in 2021, Financial Times, December 30, 2021.

- Tilley, D., “Two Unappreciated Compelling Reasons to Own Gold in the 2020s”, Asset Class Trading Blog, March 12, 2020.

- The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2021. Using a flow approach of $50 billion in annual sales along with an estimate of a roughly 20-year average holding period, yields a market cap of about $1 trillion.

- Heitner, D., “Playing Ball in the Multi-Billion Dollar Sports Collectible Market, Forbes, April 11, 2016.

- Elbaor, C., “Buyers of Maurizio Cattelan’s $120,000 Banana Defend the Work as ‘the Unicorn of the Art World,’ Comparing it to Warhol’s Soup Cans, Art World, December 10, 2019.

- Dimson, E. and Spaenjers, C., “Ex Post: The investment performance of collectible stamps”, J. of Financial Economics, 2011, vol. 100, issue 2, 443-458.

- Dimson, E. and Spaenjers, C., “The Investment Performance of Art and other Collectibles”, Chapter 10 of the book: Risk and Uncertainty in the Art World, edited by Anna M. Dempster, 2014.

- Dimson, E., Marsh, P., Staunton, M., Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2018.

- Goetzmann, W., Renneboog, L., Spaenjers, C., “Art and Money”, American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 3, May 2011, pp. 222-26 plus various working papers.

- Artprice Quarterly Global Art Market Index, data can be obtained here: https://imgpublic.artprice.com/pdf/agi.xls?ts=2020-11-17 10:19:15

- Chernow, R., “The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, 2010.

- Scheidel, W., “The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century, 2018.

- Robert A. Siegal Auction Archives, The William H. Gross Collection, Sale #1188, #1200, #1211, and #1228, 2018-2020.

Disclosure

Past Performance is not indicative of future results. The content contained within this blog reflects the personal views and opinions of Dennis Tilley, and not necessarily those of Merriman Wealth Management, LLC. This website is for educational and/or entertainment purposes only. Use this information at your own risk, and the content should not be considered legal, tax or investment advice. The reader should consult with a financial services professional regarding the suitability of collectibles in their own investment portfolio.

The views contained in this blog may change at any time without notice, and may be inappropriate for an individual’s investment portfolio. There is no guarantee that securities and/or the techniques mentioned in this blog will make money or enhance risk-adjusted returns. The information contained in this blog may use views, estimates, assumptions, facts and information from other sources that are believed to be accurate and reliable as of the date of each blog entry. The content provided within this blog is the property of Dennis Tilley and Merriman Wealth Management, LLC (“Merriman”). For more details, see the Important Disclosure.

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction