Liquid alternative funds are the new hip product sold by investment management companies. Liquid alt funds offer strategies that have been used by hedge funds, managed futures funds and private partnerships for many years with the potential to earn a higher risk-adjusted return than stocks and bonds often combined with a low correlation. Previously this space was largely off limits to small investors due to institutional-sized minimums or the need to be an accredited investor. Now these strategies are accessible to all investors via ETF and open-ended fund structures, which offer daily liquidity.

The trend towards liquid alt funds is motivated by the desire for enhanced portfolio diversification and the need to do something about low bond yields. These were the same motivations that led to the massive growth of hedge fund assets over the past 10 years as pension funds allocated to this space following the 2000 to 2002 bear market.

Pension funds were basically emulating the Ivy League endowment model, popularized by David Swensen1, who successfully employed heavy allocations to hedge funds in the previous 10 years during the 1990s. Now, after 20+ years of industry growth, individual investors are finally getting their turn to invest in alternatives. This is likely not a good thing for their portfolios.

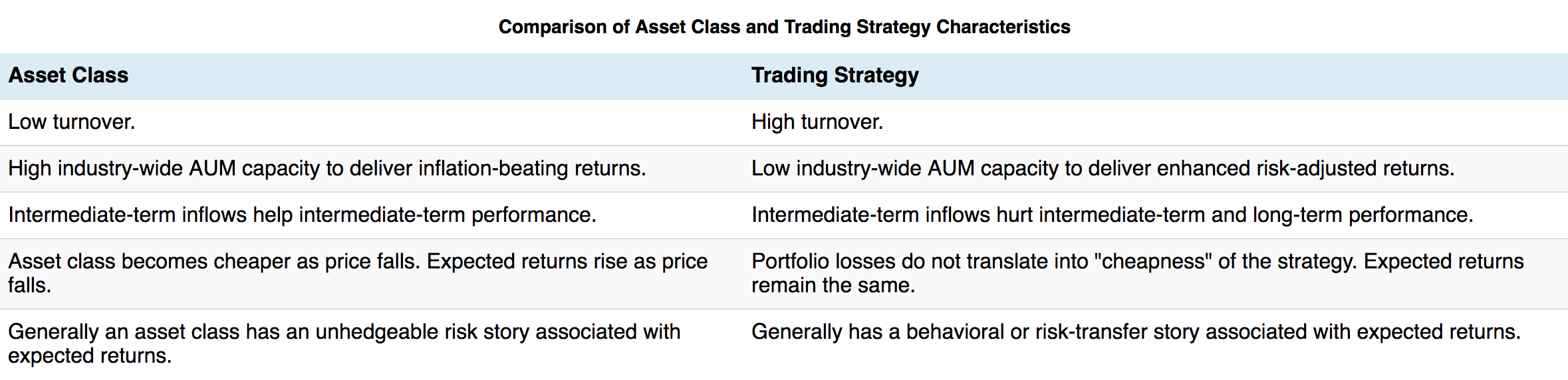

This blog is about trading asset classes, so let’s ask the following questions: Are hedge funds an asset class? What about managed futures or the various liquid alternative funds? The answer is no – I tend to refer to them as “trading strategies.” The implications of this distinction when trading and investing in asset classes are very important Asset classes have low turnover among the securities held in the portfolio. Trading strategies have high turnover, which causes liquid alt funds to lose a few relevant asset class characteristics.

Let’s compare important traits associated with each.

Turnover and Capacity

Asset classes such as equities, bonds and physical gold generally have low turnover and thus low annual transaction costs. Over the past 10 years, essentially all Vanguard U.S. and international equity index funds have annual turnover ratios of about 5% to 15%.2 The highest turnover among their equity index funds is about 30% for the small cap value asset class.2

Contrast that with the extremely high turnover associated with many alternatives: managed futures (~200% or more), equity momentum (~100%), passive commodity funds (~1000% associated with monthly rolling of contracts) and monthly option selling (~1000% for the option exposure).

Investors tend to ignore the impact of transaction costs on long-term returns. Transactions costs are typically less than 1% per year, and often much smaller, on the order of 0.1% per year or less. We also tend to trust that our investment managers are doing their best to monitor and minimize these costs.

The impact of turnover on performance is generally negative. For a given group of securities with similar liquidity characteristics, higher turnover leads to a larger portfolio fraction lost to transaction costs each year.

For a given fund, as assets under management (AUM) increases, transaction costs take a slightly higher percentage of returns each year. This is one aspect of the “capacity” problem.

There’s no disputing the above two statements. But if you try to generalize, things get a lot more complicated and difficult to prove. A high-turnover strategy in a very liquid market can have lower overall transaction costs than a lower-turnover strategy in an illiquid market. A fund manager can also adapt to managing more assets by modifying the trading strategy to reduce the impact of transaction costs.

However, I’m going to generalize the statements above to the following:

The higher the turnover, the more susceptible a trading strategy is to performance degradation as industry-wide assets grow.

Most people would agree with this statement, so it’s not revolutionary. Yet each liquid alt salesperson will have reasons why their fund is unaffected by this phenomenon. The industry-wide performance degradation process is complicated by many factors that must be considered. Is the strategy liquidity-demanding (higher transaction costs) or liquidity-providing (lower costs)? Most active strategies are liquidity demanding.

There are no mathematical formulas to calculate capacity, and even if there were, it’s also very difficult to estimate how much industry-wide assets are devoted to a strategy.

Many firms monitor their trading impact costs by measuring commissions, bid/ask spread and the market impact associated with actual trading. From actual measurements, they can engineer ways to minimize the impact of trading. As assets grow, managers have to sacrifice a bit to keep costs low, usually by diluting the factor loading the strategy was intended to exploit.

Actually, the standard measures for trading impact costs come up short. There are many subtleties and hidden costs associated with trading securities. Is the trading gameable or predictable to market makers and traders? If so, the actual cost of implementation may be much higher than a market-impact analysis would indicate. Even index funds are hit by this cost during reconstitution time.

For a particular trading strategy, such as managed futures or equity momentum, all funds generally buy the same securities at roughly the same time. Probably not the same exact day, but if Fund A is buying on Monday, Fund B could be buying on Wednesday. Fund C through Fund ZZ are purchasing the security in some distribution around these dates.

When this happens, securities to be purchased will be bid slightly higher for all funds when averaged over many trades. The same phenomenon happens with selling transactions, and this effect does not show up in standard trading cost analyses. This is the mechanism for the market to arbitrage a trading strategy into the dust bin.

As industry-wide assets grow, the buying and selling can actually cause prices to deviate from the natural short-term equilibrium price, which leads to more money-losing whipsaw trades, and lower performance for all.

Of course, no one knows what asset level constitutes too much. For a long-term investor, it probably makes sense to avoid high-turnover strategies because it’s just too difficult to know where you stand with respect to the performance degradation associated with industry-wide asset growth.

Fund Flows

As an asset class trader, I favor asset classes that have sustained and large month-after-month inflows. I tend to avoid asset classes that are facing outflows. When money flows into a low-turnover asset class, the flows tends to bid up the assets you already own. Riding this wave can be an alpha source in the asset-class trading game.

Contrast that with hedge funds. The massive amount of money allocated to hedge funds over the past 10 years has the impact of immediately lowering future returns. The same goes with any high turnover strategy such as equity momentum, passive commodity funds, managed futures and others.

Industry-wide flows into trading strategy funds are good for salespeople and fund companies, but bad for investors and portfolio managers who genuinely care about performance.

Losses and Expected Returns

When an asset class suffers a bear market, prices fall significantly, valuations improve and future expected returns rise. For instance, if the 10-year bond yield rises from 2% to 5%, a significant short-term loss will occur. Yet from that point on, the expected future return has risen from about 2% per year to 5% per year.

The same occurs with other asset classes, such as equities, real estate, currencies and physical gold and silver. As a long-term investor, I like this aspect of investing in asset classes. Developing a well-diversified portfolio of asset classes combined with annual rebalancing is a smart approach to investing for the long term.

This is not the case when a trading strategy suffers large losses. Does the strategy get cheaper or do expected returns improve? Generally the answer is no, although there are a couple of weak mechanisms for improved future performance. The first mechanism comes from the net-long exposures to equities and bonds that most hedge funds maintain, so bear markets can improve future returns somewhat indirectly because funds are holding asset classes that are now cheaper.

Another potential mechanism for improved returns is the losses themselves and subsequent fund outflows that reduce the capacity effect. This effect is second order, and I struggle to bet on it.

Risk Story

Asset classes have a risk story associated with them that provides confidence that long-term returns will outpace T-bills and inflation. Equities have the risk of recession, bear market and depression. In the 1930s, equities lost 90% of their value. For bonds, the risk premium is due to interest rate, inflation and default risk. These risks are not hedgeable, so long-term investors should expect the risk premium to be enduring.

Value stocks provide a premium return above growth stocks because they are riskier (although a behavioral finance explanation can also work here). Deep value companies have a higher cost of capital associated with them, thus expected returns should be higher. Value stocks lose more during deep recessions. Small-cap stocks should outperform large-cap stocks over the long term also because they are riskier and less liquid.

Contrast that reasoning with trading strategies. There is no risk premium associated with hedge funds if their job is to truly deliver alpha that is uncorrelated with stocks and bonds.

Momentum among asset classes is a factor we’ve used for many years. Momentum is a behavioral phenomenon caused by the very human instinct to performance chase. I’m convinced this human characteristic is very powerful and will never go away. However, the combination of momentum’s growing popularity, high turnover, and the uncertainty associated with the strategy’s capacity leads to long-term concerns about its return premium. About five years ago, we dramatically reduced the use of long-momentum as hedge fund assets exploded and dedicated momentum mutual funds were introduced. I struggle to confidently bet that momentum would add value in the future.

I wrote about commodity funds back in 2008 when these funds were very popular.3 The case for investing in commodity funds was a risk transfer story – commodity funds were helping commercial hedgers insure against a collapse in prices, thus a premium was earned by commodity investors for taking the other side of this hedging activity. However, this argument doesn’t hold if “too much” money is invested in commodity funds. At that point, the futures term structure changed such that the commodity fund investors are now the ones paying insurance – in this case, for inflation protection. Also, the trading associated with these funds is very gameable. What is the industry-wide capacity of this strategy? No one really knows, and I’m still uncomfortable making long-term allocations to commodities for this reason.

By the way, asset classes can also become too popular and overvalued. Many times in modern history, stocks have been priced to deliver a negative return over the subsequent 5- or 10-year period. Look at what Japanese stocks have done since 1990 when valuations were at extreme levels. These moments are another opportunity for an asset class trader to add value.

While I acknowledge that asset bubbles can form, which can lead to painful losses, we remain confident that the risk story associated with stocks and bonds is indeed enduring. Trading strategies have a much more uncertain future with respect to return premiums. I expect the current liquid alts trend to disappoint investors in the future.

Implications for Asset Class Traders

- We typically don’t trade “trading strategy” funds, such as hedge funds and managed futures funds. We have no trading edge associated with valuation or flows that can be used with these types of funds.

- If a lot of money is flowing into hedge funds or mutual funds exploiting a high-turnover trading approach that you currently use, it might be time to revisit the rationale for why the edge will work in the face of increased competition. It may be time to look elsewhere for a trading edge.

Implications for Investors

- The core of a diversified portfolio should consist of low-turnover asset classes. High-turnover trading strategies should generally be avoided, or kept small if there’s a burning desire to invest with a manager or trading style.

- I expect that in aggregate, high-turnover liquid alternative funds will fall short in delivering superior risk-adjusted returns. There will be exceptions, which will be difficult to predict ahead of time.

- I would focus on alternatives that are semi-liquid, low turnover, and have a clear risk-story associated with them. Reinsurance, direct lending, and direct real estate come to mind. Unfortunately, all three of these examples are not readily available to everyone.

- Some high-turnover strategies can also make sense if an investor is willing to pay for the “insurance” provided. Commodities funds used to protect against inflation spikes have many flaws, but they may provide effective insurance if inflation does indeed surge one day in the future. But over the long term, an investor must be willing to accept lower risk-adjusted returns for this peace of mind.

References

- Swenson, David, Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment, 2000.

- www.morningstar.com.

- Tilley, Dennis, “Analyst: Commodites Not Best Way To Hedge Inflation Bets”, www.etf.com, February 2008. http://www.etf.com/sections/features/3706.html.

Disclosure

The content contained within this blog reflects the personal views and opinions of Dennis Tilley, and not necessarily those of Merriman Wealth Management, LLC. This website is for educational and/or entertainment purposes only. Use this information at your own risk and the content should not be considered legal, tax, or investment advice. The views contained in this blog may change at any time without notice, and may be inappropriate for an individual’s investment portfolio. There is no guarantee that securities and/or the techniques mentioned in this blog will make money or enhance risk-adjusted returns. The information contained in this blog may use views, estimates, assumptions, facts, and information from other sources that are believed to be accurate and reliable as of the date of each blog entry. The content provided within this blog is the property of Dennis Tilley & Merriman Wealth Management, LLC (“Merriman”). For more details, please consult the Important Disclosure link here.