by Dennis Tilley | Dec 11, 2018 | Investing, Long-Term Edge

Executive Summary

In this post, I examine the popular stock market valuation tool, the Shiller CAPE. The Shiller CAPE valuation approach, based on 150 years of data, appears to have an uncanny ability to predict future S&P 500 returns.

Unfortunately, the benefits of using this tool for actual investment decisions appear to be limited. The Shiller CAPE, along with all asset class valuation measures, has the following significant weaknesses and issues.

- Selection bias has likely overstated the reliability of predicting future expected returns.

- Using CAPE to shift between equities and T-bills doesn’t enhance risk-adjusted returns.

- Using historical valuation data is susceptible to unpredictable long-term regime shifts that can devastate the effectiveness of such a tool.

When the Shiller CAPE is low, risks are high, and many competing asset classes are also priced cheaply. When the CAPE is high, competing assets also have low expected returns. It appears the S&P 500 is efficiently priced on the time scale used for value investing.

The best use of the Shiller CAPE is simply to set return expectations, specifically if valuation multiples revert to a long-term mean. Such expectations should also be contrasted with no-mean reversion return estimates, such as assuming the S&P 500 is simply priced to deliver a 3-5% premium over the current values of any of the following: T-bill yield, S&P 500 yield, 10-year treasury yield or inflation rate.

Introduction

Introduction

The primary reason I write this blog is to reexamine the variety of asset class trading approaches I’ve used for years. I don’t want to waste time implementing tools that appear useful, but ultimately fail to enhance risk-adjusted performance. In this post, I examine Shiller CAPE, which should have implications for using historical valuation charts in general and asset class valuation tools produced by firms such as GMO, Research Affiliates and many others.

The most popular stock market valuation tool right now is the Shiller CAPE ratio. The Shiller cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio divides the S&P 500 price by the average of the past 10 years of earnings.1-3 The averaging helps smooth out earnings volatility associated with recessions. Investors love this model because it’s very intuitive and appears to be quite good at predicting future equity returns.

Over the past five years or so, I’ve been reluctant to overweight U.S. stocks in my discretionary portfolios due to the belief that U.S. stocks were significantly overvalued based on the Shiller CAPE ratio. Unfortunately, that hasn’t worked as U.S. stocks have been the top performing asset class over that period. (more…)

by Dennis Tilley | Oct 31, 2018 | Investing, Long-Term Edge, Trading Edges

Executive Summary

- This is the first of a multi-part series examining the use of valuation approaches to identify future outperforming asset classes.

- I discuss why value investing is an essential and useful tool for asset class traders.

- I briefly discuss the Warren Buffett approach as the purest form of discretionary value investing.

- I clarify the distinction between fair value (a concept I’ve used to discuss short-term trading edges) and intrinsic value used by value investors.

- I briefly review the vast academic literature on mechanically value-tilted portfolios. These portfolios are typically heavily weighted towards cheap and risky assets. These cheap securities are most often fairly priced to deliver long-term returns that are superior to a market cap weighted basket of similar securities.

- Finally, I introduce Asset Class Value Investing as: identifying moments in time when an asset class appears to be irrationally mispriced based on an assessment of long-term intrinsic value.

Introduction

Introduction

As asset class traders, we must understand the current thinking built into asset class prices. Prices are generally determined by the actions of a global set of large institutions, pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, banks, mutual fund managers and hedge fund managers considering future prospects and risks. Finding trading opportunities requires us to get into the heads of these large market players.

Many large firms specialize in one or a few asset classes, while other large institutions focus their attention at the asset class level. Most organizations are too big to actively buy and sell securities; they need to act on longer time frames.

The question of assessing an asset class’s relative value is particularly topical right now. U.S. growth stocks continue to outperform all other asset classes despite being “overvalued” for the past 5 or so years. Meanwhile, international and emerging market stocks continue to sink, despite trading at a fraction of U.S. equity multiples. Furthermore, across the global stock market, the value style has underperformed growth stocks for over a decade, despite strong evidence value stocks outperform over the long term. The current market seems a lot like the late 1990s all over again. (more…)

by Dennis Tilley | Apr 27, 2018 | Intermediate-Term Edge, Investing, Long-Term Edge, Market Timing, Trading Edges, Trend Following

Large price runups, such as a gain of 100% over two years, are rare.1 In a previous blog post, I presented 10 attributes to distinguish asset class bubbles from large price runups that are justified by improving fundamentals. Those bubble attributes are:

- Heavy retail investor involvement

- New-era thinking

- Irrational valuations

- Five or more years of swiftly rising prices

- Parabolic rise in price

- Shorting is unattractive or impossible

- Social mania

- Product providers exploit excessive demand

- Leverage fuels more buying

- Bubbles are late-cycle phenomena

As asset class traders, we are especially interested in bubbles as a potential huge source of alpha when they collapse. As it turns out, bubbles are a lot tougher to exploit than it might seem. In this blog post, we’ll delve into bubble characteristics in more detail, and then investigate the best ways to trade asset classes that are experiencing a bubble.

We’ll examine bubble characteristics over the short term (plus and minus three years around the peak) and then longer term (a decade or more). When doing this sort of analysis, we need to at least acknowledge that various forms of hindsight bias can creep into such work since we are examining known price runups that ultimately crashed spectacularly.

It’s possible that we should include a few historical parabolic runups that did not ultimately pop.1 I’m hopeful that the lack of bubble attributes associated with these moves provides the justification for eliminating these from consideration, but I’m not completely sure. I may have also declared a few large up and down moves as bubbles (for instance, Chinese equities in 2007), when perhaps this price move had no more bubble attributes than a big move that ultimately didn’t end in a long period of underperformance (for example, the 1987 crash). (more…)

by Dennis Tilley | Mar 8, 2018 | Asset Classes, Efficient Markets, Investing

If you’re in the investment biz long enough, you’ll inevitably find yourselves searching for profitable ideas when an asset class is experiencing a bubble. The term “bubble” is a heavily overused term in the financial media and among professional investors. Any large price increase over a short time period, such as a 50% gain over a year, prompts a few writers, analysts or professional investors to describe the runup as a bubble. These bearish folks are typically using the term loosely without a nuanced evaluation to determine if prices have simply reflected new highly positive information.

If you’re in the investment biz long enough, you’ll inevitably find yourselves searching for profitable ideas when an asset class is experiencing a bubble. The term “bubble” is a heavily overused term in the financial media and among professional investors. Any large price increase over a short time period, such as a 50% gain over a year, prompts a few writers, analysts or professional investors to describe the runup as a bubble. These bearish folks are typically using the term loosely without a nuanced evaluation to determine if prices have simply reflected new highly positive information.

Additionally, how many times have we heard “bubble” used for assets that have experienced long-term, secular bull markets, such as U.S. or Japanese government bonds, when current prices are not experiencing anything like the bubble phenomenon? Then other folks use the term in a variety of ways to describe investor group think, such as “hedge funds are the next investment bubble,” or “there’s currently a bubble in investor complacency.”

I’m specifically interested in those moments in time, which can last months or even years, when price-insensitive buyers become ever more attracted to rapidly rising prices, thus bidding an asset class price way above fair value. It’s a time when pricing is determined by the one-way thinking associated with the “madness of crowds,” rather than the normal, efficient markets “wisdom of crowds” effect. The massive number of performance chasers overwhelms the financial resources of professional investors and traders attempting to push prices back to fair value by shorting and selling the asset class.

Even though the gap between price and fair value grows ever larger, uncertainty about when the market will top and how much further the price will rise creates a situation where the risk-reward of shorting the asset class becomes very unattractive. The arbs, who are usually pushing prices back to fair value, then step away, or perhaps even join the crowd. Other opportunistic professional investors join the crowd by creating new products and/or new firms to exploit the attractive optionality associated with easy money raising and rapidly rising prices.

Bubbles have occurred about once a generation throughout human history, as new investors enter the market with no experience with how bubbles eventually burst. Examples of the large bubbles include the NASDAQ bubble in the late 1990s and the Japanese stock market bubble in the late 1980s. The current bitcoin and cryptocurrency craze has all the attributes of a bubble.

Many Rapid Price Increases Are Not Bubbles

Just because an asset class has a large and rapid price run doesn’t mean it’s mispriced. One or two U.S. industry groups often have a yearly gain of greater than 50%. Most often, prices have increased to reflect unexpected improved future earnings. Also, most bull market tops don’t have a bubble associated with prices. The topping process is more drawn out as the collective wisdom is formed by market players generally using reasonable judgment of future prospects. Prices ultimately collapse when investors sense an emerging bear market or recession.

Eugene Fama, the Nobel-Prize-winning champion of the efficient markets view, believes there is no such thing as bubbles. Bubbles are only known after the fact, when there’s been a large collapse. Careful analysis of large price increases shows that many, perhaps even half, are never followed by a collapse.1 Simple price formulas for defining a bubble, even the approach used by the famous bubble studiers GMO,2,3 are not enough. We need more information. (more…)

by Dennis Tilley | Dec 18, 2017 | Investing, Long-Term Edge, Technical Analysis, Trading Edges

Often in trading we become totally engrossed in searching for short-term opportunities with a hyper-focus on news flow and daily price movements. Occasionally it’s good to drastically alter time frames, especially if your creativity has dried up on short-term ideas. One way to search for new trades is to scan asset classes that have performed the worst over the previous decade. This is especially interesting when there’s been a large divergence of performance in asset class returns over the previous 5 to 10 years.

Often in trading we become totally engrossed in searching for short-term opportunities with a hyper-focus on news flow and daily price movements. Occasionally it’s good to drastically alter time frames, especially if your creativity has dried up on short-term ideas. One way to search for new trades is to scan asset classes that have performed the worst over the previous decade. This is especially interesting when there’s been a large divergence of performance in asset class returns over the previous 5 to 10 years.

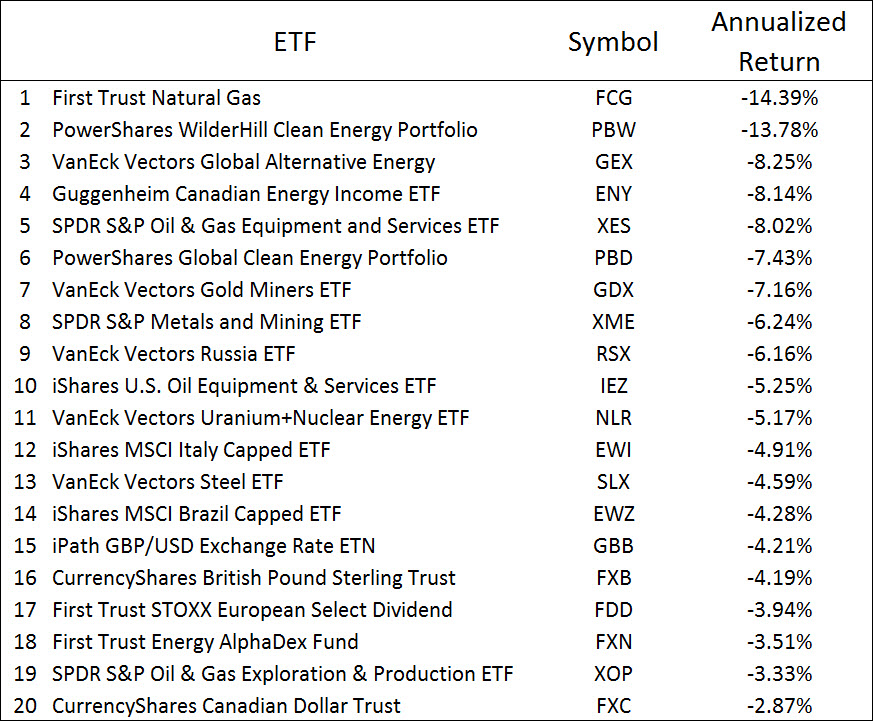

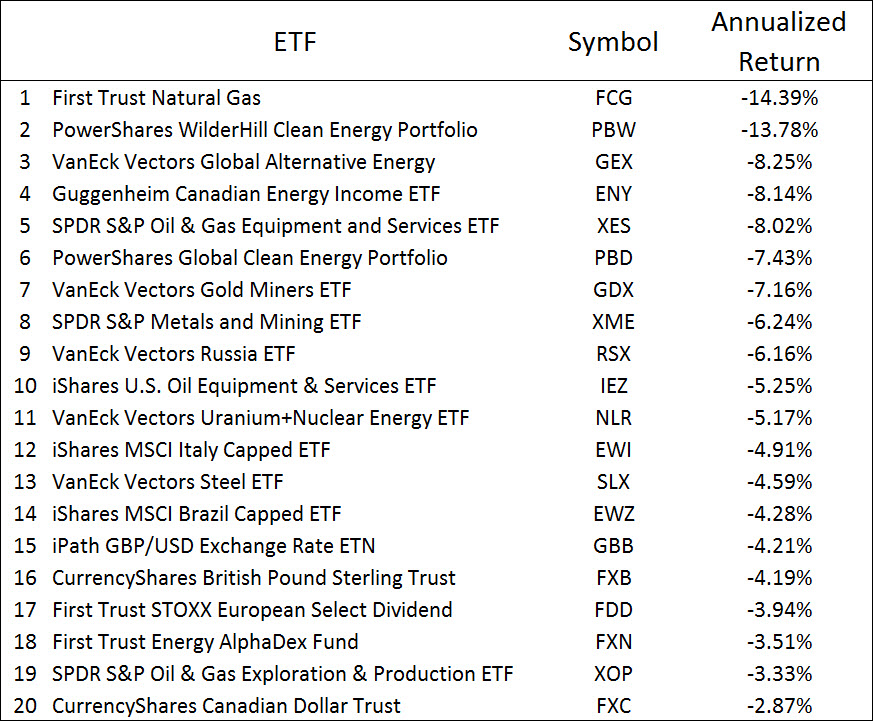

Table 1 shows a ranking of the worst-performing ETFs by 10-year annualized returns as of October 31, 2017. When tabulating this ranking, I excluded the ProShares daily leveraging funds and commodity exchange traded notes. For comparison, the S&P 500 returned 7.51% per year during this time frame. This list contains many ETFs in the energy space, with a few niche asset classes (clean energy, gold miners, steel and nuclear), country funds (Russia, Italy and Brazil) and two currencies (British pound and Canadian dollar).

Table 1: Worst-performing U.S. ETFs based on 10-year annualized returns, as of October 31, 2017. (Note: S&P 500 return over same period was 7.51%/year). Source is Morningstar.

Often these asset classes were popular many years ago, but as the terrible performance persisted over a decade’s time, more and more traders and portfolio managers shifted their focus to better-performing asset classes. With a niche asset class, such as gold mining or solar energy stocks, the last remaining holders are the enthusiasts (gold bugs), index funds and retail investors owning such a small position that to them it’s easier to ignore rather than take a loss on a sale. (more…)

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

If you’re in the investment biz long enough, you’ll inevitably find yourselves searching for profitable ideas when an asset class is experiencing a bubble. The term “bubble” is a heavily overused term in the financial media and among professional investors. Any large price increase over a short time period, such as a 50% gain over a year, prompts a few writers, analysts or professional investors to describe the runup as a bubble. These bearish folks are typically using the term loosely without a nuanced evaluation to determine if prices have simply reflected new highly positive information.

If you’re in the investment biz long enough, you’ll inevitably find yourselves searching for profitable ideas when an asset class is experiencing a bubble. The term “bubble” is a heavily overused term in the financial media and among professional investors. Any large price increase over a short time period, such as a 50% gain over a year, prompts a few writers, analysts or professional investors to describe the runup as a bubble. These bearish folks are typically using the term loosely without a nuanced evaluation to determine if prices have simply reflected new highly positive information.

Often in trading we become totally engrossed in searching for short-term opportunities with a hyper-focus on news flow and daily price movements. Occasionally it’s good to drastically alter time frames, especially if your creativity has dried up on short-term ideas. One way to search for new trades is to scan asset classes that have performed the worst over the previous decade. This is especially interesting when there’s been a large divergence of performance in asset class returns over the previous 5 to 10 years.

Often in trading we become totally engrossed in searching for short-term opportunities with a hyper-focus on news flow and daily price movements. Occasionally it’s good to drastically alter time frames, especially if your creativity has dried up on short-term ideas. One way to search for new trades is to scan asset classes that have performed the worst over the previous decade. This is especially interesting when there’s been a large divergence of performance in asset class returns over the previous 5 to 10 years.